There are quite a few academic and quasi-academic studies in which statistical analysis seems to be employed as a substitute for thinking. It is, perhaps, fairly understandable why some people are tempted by the allure of numbers. Those mysteriously complex formulae, mindnumblingly boring statistics and obscure mathematical notations lend a magical aura of scientific objectivity and plausibility to even the most patently absurd claims.

There are quite a few academic and quasi-academic studies in which statistical analysis seems to be employed as a substitute for thinking. It is, perhaps, fairly understandable why some people are tempted by the allure of numbers. Those mysteriously complex formulae, mindnumblingly boring statistics and obscure mathematical notations lend a magical aura of scientific objectivity and plausibility to even the most patently absurd claims.

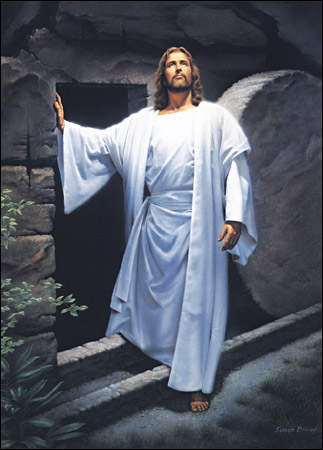

What gets me talking about this at this moment is my dumbfounded reading last night of an article published by Timothy McGrew and Lydia McGrew, entitled “The Argument from Miracles: A Cumulative Case for the Resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth” (2009). In this article, the McGrews utilize Bayesian probability in order to argue to the “scientific” conclusion that the probability of the resurrection of Jesus is a “staggering” 100,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 to 1.

Are you staggered? overwhelmed? swooning? Were you previously skeptical about the Christian claim that Jesus was resurrected, but now you’re feeling pretty silly? Perhaps not.

There is nothing new about these kind of claims. You can find similar claims in populist apologetic works ranging from Robert Anderson’s The Coming Prince to Josh McDowell’s Evidence That Demands A Verdict. And in every case, the flimsy basis for the odds is covered over by meaningless statistics that are intended only to impress. What is disturbing about the McGrews’ article is that it appears in a volume published by academic publisher, Wiley-Blackwell, and is typical of the approach of those trying to “resurrect” that impossibly inconclusive field known as Natural Theology. While both of the editors of the volume are academics, one, William Lane Craig, is better known for engaging in popular apologetic debates, and the other, J.P. Moreland has recently disclosed that he once “had an encounter with three angels.” This descent of purportedly academic publications and fields to the field of popular apologetics has its counterpart in recent biblical studies publications where the line between the apologetics and scholarship is increasingly hard to draw. Essentially apologetic works such as N.T. (Tom) Wright’s The Resurrection of The Son of God and Joseph (“The Pope”) Ratzinger’s Jesus of Nazareth have been widely received within New Testament studies, a field now dominated by U.S. Southern Baptist Seminaries and Universities – a state of affairs which has meant that even a book as out-of-touch with scholarship as the Pope’s Jesus of Nazareth could be largely uncriticized within the field and in fact championed by scholars in the response volume, The Pope and Jesus of Nazareth: Christ, Scripture and the Church (2009).

The major trick Timothy McGrew and Lydia McGrew pull when they produce their tremendous, if not entirely fanciful, odds for the resurrection of Jesus is to cover up the substantial issues regarding the resurrection of Jesus in layers of probability formulae. Moreover, by already assuming the accuracy of the Gospel accounts, the paper is as close to circular reasoning as one can get, without being completely circular. The assumptions pragmatically, if not technically a priori, rule out in advance any alternative explanations, because the Bible is assumed to provide the most accurate idea of what really happened: the major implication being that alternatives are already effectively deemed less likely. The whole exercise is deeply and unavoidably farcical. Therefore, as you read the following formulae, bear in mind that what their claim all boils down to is one very old and tired apologetic claim: if we accept the Gospel stories as credible eyewitness accounts (which is itself at best a highly disputed contention), the best explanation of what really happened is exactly what the Gospels claimed to have happened.

First up, here is the McGrews’ statistical formula for, in effect, saying “Given what the Bible says, I reckon the resurrection really happened:”

P(F1 & … & Fn|R) / P(F1 & … & Fn|~R) >>1

where P=’probability of’; F=’fact’; and ‘R’ is ‘resurrection’

The McGrews then provide a derived formula for multiple independent facts, which, again, basically says, “Given what the Bible says, I reckon the resurrection really happened:”

P(R|F1 & … & Fn)/P(~R|F1 & … & Fn) = P(R)/P(~R) x P(F1|R)/P(F1|~R) x … x P(Fn|R)/P(Fn|~R)

The McGrews then consider three “facts” (taken from the Bible) in order to apply this formula: the reports of the resurrection by the women who visited Jesus’ empty tomb (“W”); the testimony of the disciples (“D”); and the conversion of Paul (“P”, again). And this provides the following formula, which basically equates to the claim, “Given what the Bible says, especially about those women, disciples, and Paul’s conversion, I reckon the resurrection really happened:”

“P(R|F1 & … & Fn)/P(~R|F1 & … & Fn) = P(R)/P(~R) x P(W|R)/P(W|~R) x P(D|R)/P(D|~R)x P(P|R)/P(P|~R)

For reasons that escape both me and the authors themselves, the probability concerning the women is then assigned odds of 100:1, the disciples each 100:1, and Paul’s conversion 1000:1. As there are 13 “disciples” mentioned in the stories, the McGrews multiply the 100:1 odds for each one of the disciples – even though they all appear in the same story – to get 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000:1. And if you multiply that by the women’s odds (100:1) and the odds from Paul’s conversion (1000:1), you get another five zeroes: 100,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 to 1.

Which is a real scientific way of saying, “The Bible says it, I believe it, that settles it.”

wotz the definition of ‘academic’?

Be imaginative, creative, artistic, poetic if you like, how divine.

Wow. Great piece. I think if anything sort of illuminates the way that thresholds of what counts as acceptable evidence can be manipulated by a burning desire for something to be true, this would be it.

seems like he did a lot of work to try to make his magical thinking sciencey sounding.

so “A” for effort, but “F” for the wrong conclusion, despite showing the work